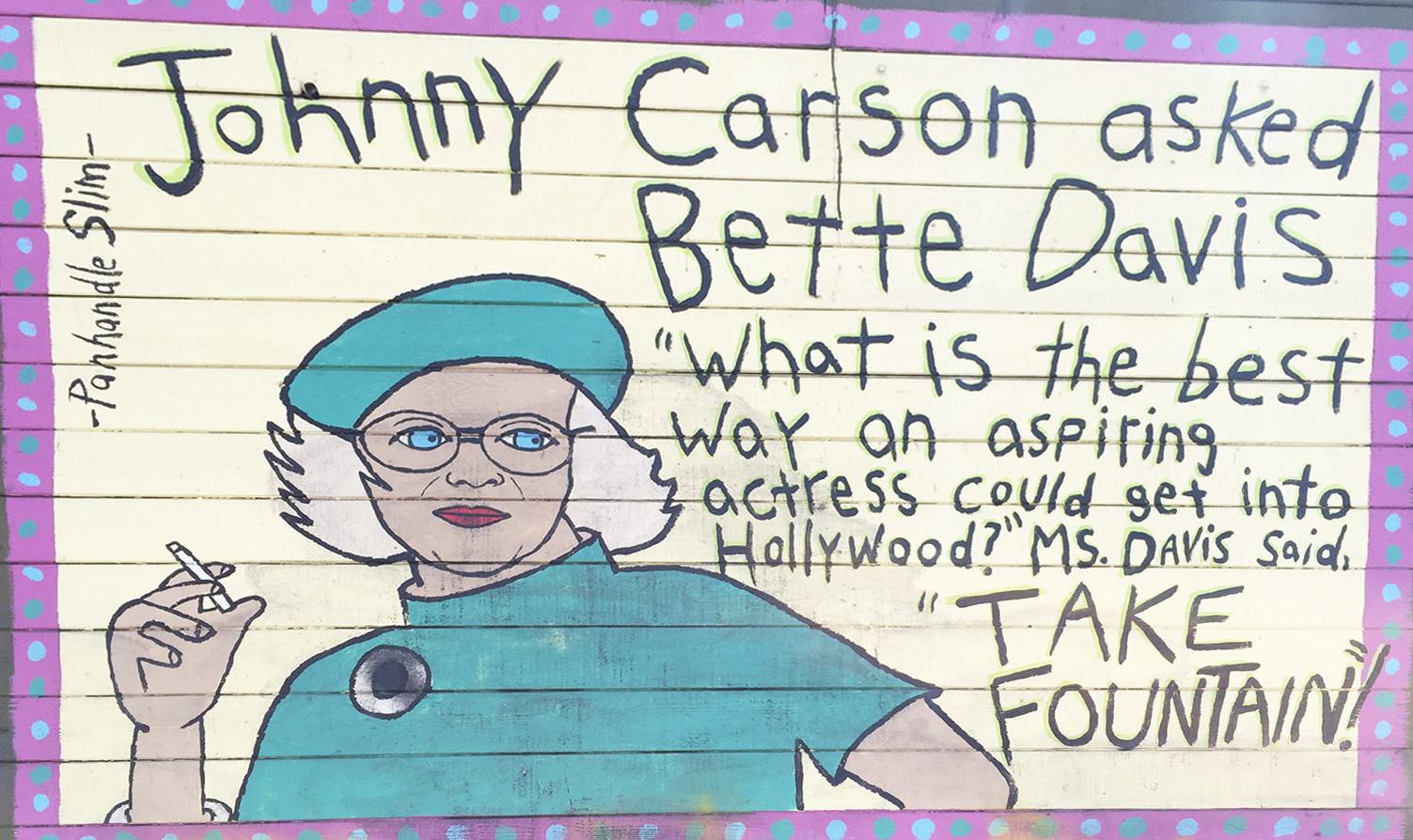

Apparently Johnny Carson once asked Bette Davis to tell him the best way for a young actress to get into Hollywood. Her response, now a hot but still deliciously subpop tagline for the tens of thousands of industry-adjacent hipsterati who have tattooed it into their flesh, named trendy cultural objects for it, painted murals incorporating it, splashed it across Twitter feeds and everywhere, was “take Fountain.”1

This is an excellent joke, but it’s not a robust joke. The setup line requires very specific phrasing in order both to sound natural and to allow for the joke’s kicker, which is the conflation between physical arrival in a space and the various metaphorical tropes that that space can represent. One can’t mention careers, e.g., or the required conflation fails. Even “get to Hollywood” is risking failure.

But also one can’t spoil the joke by betraying the punch line in the setup question , which the mural version shown above comes pretty close to doing. “Make it to Hollywood” would be an abject failure. The setup is so delicate that it seems likely Carson’s question was careful designed to match the forthcoming response, which was probably then not exactly spontaneous.

The joke’s very iconicity means it’s been extensively subjected to the folk process, which always increases cultural robustness. The payloads carried by folk culture must be tolerant of reproduction errors and the folk process consequently selects strongly for that. The fact that this joke has survived and even flourished given its delicacy suggests that it carries immense power and is therefore capable of serving a diverse set of purposes.

Another thing that the folk process does is embed the multilayered concerns of all the people involved into its products. Folk culture gets passed along, remembered, and modified because it means something to the people passing it. One way that jokes function as tools is by imposing a world-view on their listeners consisting of some assumptions that are required for the joke’s humor to click. The folk process ensures that that world-view is useful to many. To understand the kinds of things this joke can effect, the uses to which it can be put, it’s necessary to see it in the context of the picture of the world its humor assumes.

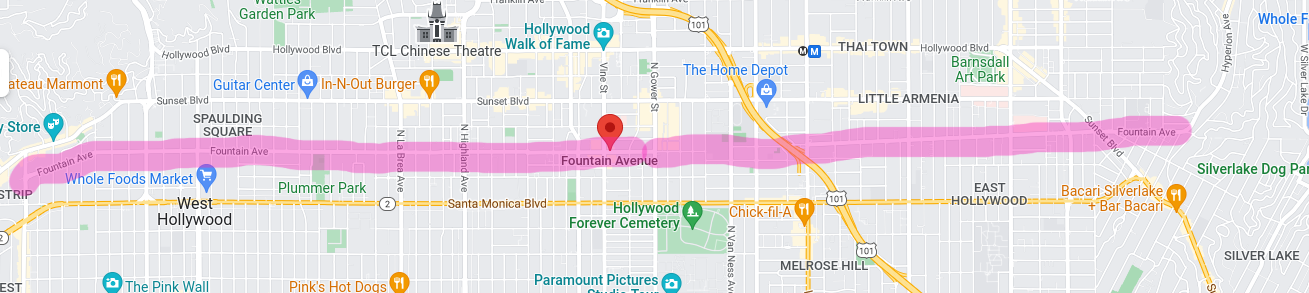

A map of West Hollywood, Hollywood, and East Hollywood showing the entire length of Fountain Avenue in Los Angeles.

The first part of that context is factual. Fountain Avenue is a short, only six miles long, east/west street that runs from West Hollywood through Hollywood proper and ends somewhere in Silver Lake. It’s not one of this City’s world-famous avenues like Santa Monica Blvd or L. Ron Hubbard Way. It’s not locally famous and doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. Native Angelenos who don’t spend much time in Hollywood may not know it and certainly don’t know it well. Also as far as I can see Fountain is unique among streets of its size in that it terminates abruptly at both ends.2 It’s not really a through street even though it serves as one in greater Hollywood. It doesn’t invite the whole world in.

On the other hand in the context of Hollywood the physical location, Fountain is intrinsically important. Everyone who spends time in Hollywood knows this street, but it doesn’t serve many neighborhoods. Echo Park is about as far east as Fountain matters, and Beverly Hills to the west, where Fountain’s an excellent alternative to either Santa Monica, Sunset, or Hollywood Boulevard. Part of the pleasure this joke provides lies in the sharing of inside knowledge, not only of how Fountain functions as a street in real-life LA but also in the immediate understanding that Hollywood is a physical neighborhood as well as an iconic synecdoche.3

And Fountain is a consistently charming street, but also a functional street, a street that has played a substantial role in the industry’s development in Los Angeles. Its west end is full of century-old apartment palaces set up to house the thousands of unattached young people on whom the industry, then as now, thrived, and to allow capitalists to recapture some of the money as rent that they’ve had to pay these young folks for their labor over the years. In Hollywood proper Fountain is still residential, still an apartment-centric street, although on a more modest scale.4

The less ritzy Fountain-adjacent apartment buildings of East Hollywood played the same role for those on a smaller budget, like Betty Schaefer of Sunset Boulevard, who famously grew up on Lemon Grove Avenue near Paramount because her dad was in the trades. From any point on Lemon Grove Fountain is an eminently reasonable way to get to Hollywood and it’s easy to imagine a perky aspirer like Nancy Olson herself must once have been tootling west in a cute little car. Like most of that part of the City the further east of Vermont one gets the smaller the scale of the apartments and the greater the number of single family homes.5

One can imagine Davis’s young actress having started her career in either East or West Hollywood, maybe bankrolled by her parents, and gradually moving east along Fountain until she made it big enough to break out of the one-dimensional rut and head north to the Hills. An audience which understands this implicit career trajectory and the appropriate geography within which it is to be enacted is also essential for the joke to work.6

A useful technique for understanding jokes is to consider which of their elements could be swapped out and with what. Usually substitutions break the joke and the ways in which this happens provide insight into the joke’s mechanics. In this case it’s impossible to change the street. First of all Fountain is the Goldilocks of east/west streets through Hollywood with respect to this joke. Anything bigger, Santa Monica Blvd, Melrose, Sunset, Hollywood Blvd, and the whole world’s heard of it and the joke fails. With smaller streets either no one’s really sure if they go through like De Longpre or Selma or else they’re obscure and minuscule like Homewood, Afton, Leland.

Only a few significant north/south streets serve Hollywood directly, but there are two superficially plausible alternatives. Cahuenga Blvd is a thoroughly reliable route into Hollywood from the Valley, and it shares some significant qualities with Fountain. It’s locally famous. Everyone in Hollywood and whatever parts of the Valley it goes through knows it and people outside of those areas may not. But during most of Davis’s career the route into Hollywood along Cahuenga was mostly farmland until one reached the hills, which were and are far too rich to make the joke work.

Cahuenga wouldn’t have been useful to aspiring actresses in that period, which began in 1929 and spanned 60 years. It doesn’t, or at least didn’t, traverse an appropriate geography. Even if now Cahuenga would function perfectly well in this joke, it wouldn’t have for the time period in which Davis likely formed her understanding of the city. But then there’s Crenshaw/Rossmore/Vine, which is an incredibly efficient way to get into Hollywood from huge swaths of Los Angeles the South Bay cities.

It’s true that Vine Street is world-famous and only exists within Hollywood and would therefore spoil the joke. Also Rossmore is far too obscure. However, Crenshaw Blvd, although world famous, would nevertheless function in the joke with respect to the insider knowledge that it connects effectively to Vine. Not only that, but it did as early as 1916, when the south end of Crenshaw was at Adams, a little less than six miles from the corner of Hollywood and Vine. That is to say, about the entire length of Fountain Avenue.

Not only is the distance spanned similar but the local physical geography is as well. Crenshaw had and has a wide variety of housing choices so that people aspiring to act can and could then find Crenshaw-adjacent places to live to suit almost any LA-viable budget. And surely Davis knew this. Everyone who spends time in Hollywood does, if only because it’s also part of a useful surface route to the airport.7 Nevertheless, Crenshaw wouldn’t have worked in the joke for Davis or any audience roughly contemporary with the span of her career.

The joke would have failed, would still fail, in fact, because the people who would have taken Crenshaw into Hollywood, who would take it now, weren’t the aspiring actresses Davis was talking about. Her mental geography of the city, at least so far as she and Carson deemed it appropriate for public presentation, didn’t include a space for aspiring actresses coming up from the south. And neither did Carson’s, for that matter. Like I said it seems unlikely to me given the delicate requirements of the setup line that Carson didn’t know it was coming. It had to have felt as consistent with his idea of the city as with hers. Their aspiring actresses didn’t live down there. And, you know, they mostly still don’t.

Davis’s aspiring actresses were as white as Hilary Duff or the industry itself but folks coming up from South LA decidedly are not.8 For the first third of Davis’s career it was literally illegal for nonwhite people to live anywhere near Fountain. She was already forty years old when Shelley v. Kraemer put an end to enforcement of those rules, although it didn’t make Hollywood immediately less white. Also Rossmore runs through the heart of Hancock Park, an ultra-ritz neighborhood primarily known for burning a cross on Nat King Cole’s lawn to welcome him as their first Black resident.9 Even if the industry had been open to aspiring actresses commuting north on Crenshaw the actresses might not have made it through Hancock Park alive, another point of failure for the substitution.

Both Davis and Carson had long successful careers, neither of which would have been possible had they not been white. Not because they were untalented, but because so many others were and are as talented but weren’t able to get to Hollywood no matter which physical streets they used. Colin Kaepernick‘s career trajectory shows that talent alone isn’t enough to make it in show biz, it’s also required to support the approved narrative.10 Whether Kaepernick’s forerunners were cut out of the industry or whether they self-censored to get in and stay in, their stories are probably mostly invisible now, but no less real and certainly no less essential to the existence of careers like Davis’s, like Carson’s.

Davis’s joke, like all jokes, conjures up a world in which the participants feel at home, in with the in-crowd. On its surface this world is one where we share an understanding that Hollywood is a physical place as well as a symbol for the Industry and we share some knowledge, of the utility of Fountain as a route. As a physical place Hollywood has more and less efficient ways to transport one’s body there, which symbols fail to have. A deeper look reveals a haunting racial geography on which the joke relies, a racial geography created and maintained by violence.

This racial geography haunts me whether or not it haunts those who quote Davis. But I know I can be overreactive, maybe its power is fading now, too removed from the present to influence the joke’s effect, irrelevant. I mean, clearly there’s a plausible argument for that position. There are plenty of folks quoting Davis who have no idea that race has anything at all to do with the world her joke evokes. Does anyone seriously think that Hilary Duff knowingly had a white supremacist punch line tattooed on her arm?

And maybe it is that simple, but I don’t think so. The area that Fountain funnels into Hollywood is bitterly contested racial territory even today, as is the Crenshaw Corridor. The 2021 Battle of Echo Park, which lies squarely in Fountain’s catchment area, was another skirmish in the same unending war over who has access to the streets of this city, who is allowed to choose their destinations freely, whether they be physical, aspirational, or spiritual. Davis’s joke is still doing some dirty work in the world regardless of the intentions of its users.

These are our streets, as the chant has it, and that’s absolutely the truth. But until it’s also both the whole truth and nothing but the truth I want to remember in every context that streets aren’t neutral carriers, they’re not open to all and they don’t lead everyone to the same destinations. They have beginnings and endings, restrictions and barriers. They join worlds together or separate them. Streets are both weapons and tools. I no longer enjoy this joke.

- Does anyone have a clip of this moment? I couldn’t find one.

- A lot of streets in Hollywood do this, I think because Hollywood was platted or separately from LA and for whatever reason they didn’t make all the streets go through. Hollywood Blvd does the same thing, although of course it’s much more famous then Fountain.

- When I first left LA for college at the age of 17 I was constantly surprised how few people outside the city knew that Hollywood is a physical place. I continue to be surprised, actually.

- At least up until about 10 years ago. Like many similar parts of Hollywood the central segment of Fountain has been filling up with apparently ritzy multi-use buildings. I don’t know of course but I have a feeling that in another 20 years they’ll look as crappy as the formerly luxe-adjacent dingbats around them.

- As long as one can ignore the seething and pernicious miasma of Scientology emanating from Big Blue up near Vermont.

- I’m not claiming these are all the ways in which the joke functions. I’m sure they’re not, and given the difference between my age and Bette Davis’s along with the essential fact that she’s a woman and I’m a man I’m also sure I’m incapable of seeing all of them. Just for instance some of the joke’s effect may well have been meant to follow from the shock at hearing Davis, as a woman, nonchalantly confess to driving, or at least navigating. Perhaps this was weird enough to provide a laugh when Davis’s ideas about the world had already firmed. There could be any number of things like this and I’d never know.

- Crenshaw to Stocker to La Cienega to whatever you like out there.

- Yes, of course Palos Verdes, but it’s too far away to affect the argument. No one aspiring to anything is commuting anywhere from out there. On the other hand this is changing with the ongoing gentrification of West Adams and eastern Culver City. In ten years if things go on like this the joke may well make more sense as “Take Crenshaw.”

- There’s a good account of this in Peter Levinson’s biography of Nelson Riddle.

- Sports is show biz, everyone know this.